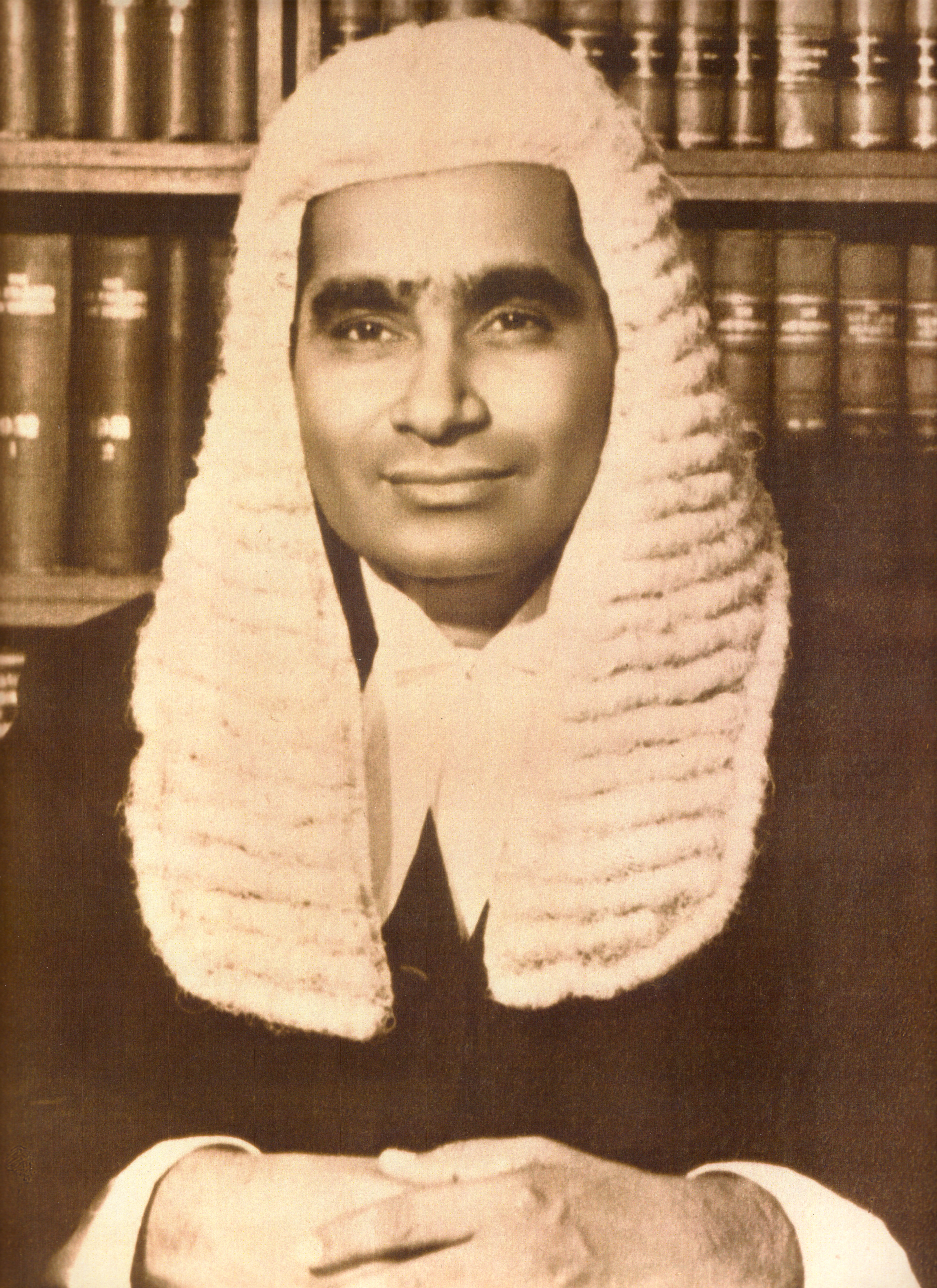

In the annals of Sri Lankan legal history, few figures command as much respect and admiration as S. Nadesan QC—a lawyer, judge’s counselor, human rights champion, and senator who lived by the principle that principle matters more than personal triumph. Though he passed away on December 21, 1986, his legacy continues to inspire lawyers and human rights activists across generations.

From Student to Advocate

Born on February 11, 1904, in Anaicottai, Jaffna, Somasundaram Nadesan’s early life hinted at the unconventional path he would take. A scholarship student at Royal College, Colombo, he abandoned his university studies—failing his Physics Practical exam—to pursue teaching, then law. His detour, however, was not a failure but a redirection toward his true calling.

Nadesan was admitted to the Bar in 1931 with no established connections in the legal profession. What he lacked in networks, he made up for in determination. A fortuitous case representing a chettiar in the Court of Requests became his breakthrough. His skillful handling of the case impressed the business community, and soon he had established a thriving practice through sheer merit and hard work.

The Making of a Lawyer

Even before his legal career began in earnest, Nadesan was shaping his philosophy. A founding member of the Jaffna Youth Congress (JYC) in 1924, he championed radical ideas—calling for poorna swaraj (complete independence) when southern political leaders were still content with dominion status. The JYC stood for a united, secular Ceylon committed to universal values and the elimination of caste barriers. This idealism would permeate everything Nadesan did as a lawyer.

Throughout his career, Nadesan developed formidable expertise spanning criminal law, civil law, constitutional law, labour law, human rights, and defamation. But it was not merely technical brilliance that set him apart—it was his incorruptible commitment to justice.

A Lawyer for the Voiceless

When trade unions faced industrial disputes, they turned to Nadesan. He represented them regularly, never accepting payment. It was, as one colleague noted, a genuine labour of love. Similarly, he took on cases defending sedition charges against trade unionists, challenging government overreach, and defending the fundamental rights of minorities.

In 1943, Nadesan secured the acquittal of Abdul Aziz, a trade unionist facing sedition charges, despite facing a hostile bench. His argument—that criticism of government anti-Indian policies did not constitute treason—demonstrated a lawyer unafraid to challenge authority when justice demanded it.

The Peter Pillai Foundation honored him in 1983 for his contributions to human rights and social justice. In his acceptance speech, Nadesan encapsulated his philosophy:

“The Rule of Law is the foundation of democracy. Democracy is a moral concept. It is something which is pledged to the defence of truth and justice. If we compromise with evil, with injustice, with untruth, we may gain a temporary advantage, but permanent danger will result.”

Landmark Cases: Standing for Principle

Nadesan’s career was marked by several landmark judgments that shaped constitutional jurisprudence:

Kodakan Pillai v. Mudanayake challenged the disenfranchisement of Indian Tamils under new citizenship laws. Nadesan successfully argued that the legislation violated the “solemn balance of rights” in the Soulbury Constitution protecting minorities—though the Privy Council ultimately overturned the victory.

Thiagaraja v Karthigesu established the courts’ authority to issue declarations regarding personal status—a foundational principle in family law.

In the Press Council case, Nadesan argued that the Press Council Bill was fundamentally inconsistent with the First Republican Constitution. The Constitutional Court’s Chairman observed it was the most important case he’d heard during his tenure.

Nadesan’s defence in Saturday Review cases protected freedom of speech and expression during times of government pressure and emergency regulations. Though the Supreme Court ultimately dismissed the petitions, these cases became important legal reference points in defending press freedom.

Perhaps most dramatically, during the turmoil of Black July 1983, when violence against Tamils raged across the country, Nadesan insisted on attending court for the pronouncement of judgment in Hewamanne v. de Silva. “I have never kept judges waiting,” he declared. When he arrived at Hulftsdorp, no judges were present—they arrived an hour later, clearly after being informed of his attendance.

The Judge’s Counsel

What set Nadesan apart was not just his legal acumen but his character. Esteemed seniors of the Bar, including Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, fondly called him “Boss”—a term capturing both respect for his judgment and affection for his character.

Chief Justice Sharvananda said of him: “It can be said of only Mr. Nadesan that he was an all-rounder, quite at home whether it be in the Privy Council, Supreme Court, Election Court, the Income Tax Board of Review or Industrial Arbitrator or Parliamentary Committee.”

For nearly nineteen years, Nadesan served as standing counsel for the Lake House group of newspapers. The newspaper’s editor, Esmond Wickremesinghe, had “implicit faith in Nadesan as a lawyer. His tactics, his court craft—all suited the limitless situations that arose in journalism.”

A Senator’s Voice

Elected to the Senate in 1947 as an independent with no party affiliation, Nadesan took his responsibilities seriously. His speeches were incisive and illuminating. In 1952, following a violent hartal, he delivered what historian James Manor described as “a devastating assault on the government’s conduct during the hartal and on the draconian public security legislation which it had rushed through parliament.”

Remarkably, Nadesan personally visited refugee camps to verify the welfare of displaced people—risking his safety when a mob stopped cars searching for Tamils. Only his Sinhalese driver’s quick thinking saved him from harm.

After the 1971 insurrection, Nadesan used his curfew pass to gather accurate information about what had occurred. His subsequent Senate speech—delivered 39 days after the outbreak—reflected his personal anguish and passion for truth. According to some accounts, this speech was a prelude to the formation of the Civil Rights Movement in 1971.

In 1954, he delivered a forceful speech condemning the forcible removal of Rhoda Miller de Silva, an American citizen, who was taken to the airport and placed on a plane without her husband’s knowledge. His emphasis on fundamental rights and family life helped galvanize international support for her return.

The Man Behind the Barrister

Unlike many senior lawyers, Nadesan was generous to his juniors, acknowledging their efforts and even praising them in court. When C. Ranganathan entered the Bar four years after Nadesan, he found a mentor ready to help him establish himself.

A chronic diabetic in later life, Nadesan recovered from a coma by adopting a rigorous regime of exercise and dietary discipline. His mantra became simple: “Eat fruits, vegetables, and nuts.” Those visiting his chambers were served carrot or pineapple juice and nuts for refreshment.

He lived simply but deliberately, treating work as worship. Whether he succeeded or failed in a case mattered less than the principle he stood for. As one admirer wrote: “He lived—and died—on his feet.”

A Life Guided by Philosophy

Nadesan lived by the philosophy of the Bhagavad Gita, encapsulated in Lord Krishna’s words to Arjuna: “To action man has a right, but not to the fruits thereof.” He met success and defeat with quiet equanimity, believing that struggling with integrity was more important than personal triumph.

He was fundamentally a man of conscience. When charged with breaching parliamentary privilege for his articles criticizing Parliament’s treatment of the Ceylon Observer editor, he was acquitted. His experience and foresight in understanding the separation of powers ultimately validated his defence.

Legacy: An Enduring Beacon

S. Nadesan died at age 81 in vibrant health, physically fit, and intellectually alert—a man who had lived on his terms, guided by principle rather than expediency. Though forty years have passed since his death, his legacy remains luminous:

- He demonstrated that excellence in law requires not just technical brilliance but moral courage

- He showed that standing for unpopular causes strengthens rather than weakens the rule of law

- He proved that a lawyer can serve both the wealthy and the voiceless, and that justice demands both

- He lived the democratic principle that the foundation of a free society is the rule of law—not the rule of convenience

As Sri Lanka continues to grapple with questions of justice, human rights, and constitutional governance, Nadesan’s life remains a master class in principled action. He reminds us that what we stand for matters infinitely more than what we gain from standing.

In the end, Nadesan was what the law aspires to produce but so rarely achieves: an extraordinary human being who used his gifts not for personal aggrandizement but for the pursuit of truth and justice. His legacy is not measured in victories won, but in principles upheld—and in the countless lives touched by a lawyer who believed, without reservation, that integrity is the highest calling.

S. Nadesan QC (1904-1986) remains an inspiration to all who believe that law is a noble profession, and that courage in defence of justice is the highest form of courage.

References

Primary Sources

- Hameed, R. (2025). “S. Nadesan QC: An Enduring Legend.” Colombo Telegraph, December 21, 2025. Retrieved from https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/s-nadesan-qc-an-enduring-legend/

Constitutional & Legal Documents

- Soulbury Constitution (1947). Constitution of Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

- Ceylon Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Act, 48 of 1949.

- Citizenship Act, No. 18 of 1948.

- First Republican Constitution of Sri Lanka (1972).

- Sixth Amendment to the Constitution of Sri Lanka (1983).

- Parliamentary (Powers and Privileges) Act.

- Emergency (Miscellaneous Provisions and Powers) Regulations (1983).

Landmark Cases

- Abdul Aziz v. The Crown, (1943) – Sedition charges defense.

- E.L. Senanayake v. Navaratne, Privy Council – Election petition jurisdiction case.

- Kodakan Pillai v. Mudanayake – Citizenship rights and electoral qualification case (Soulbury Constitution challenge).

- Thiagaraja v. Karthigesu – Declaratory remedy regarding personal status.

- Press Council Case, Constitutional Court – Freedom of the press and constitutionality of Press Council Bill.

- Ratanasaro Thero v. Udugampola – Fundamental rights violations by police (Pavidi Handa case).

- Visuvalingam v. Liyanage – Saturday Review cases; fundamental rights and freedom of expression.

- Hewamanne v. de Silva – Parliamentary privilege and contempt of court.

- Attorney General v. Samarakkody – Parliamentary privilege case.

Historical & Contextual References

- Manor, J. (1989). The Expedient Utopian: Bandaranaike and Ceylon. Cambridge University Press. [Referenced for the 1952 hartal speech description]

- Wickremesinghe, S. (1996). The Road to Justice: Reflections on the Legal Profession in Sri Lanka. [Context for CRM formation, 1971]

- Mason, G. George Mason’s Memoirs – Referenced for Lake House newspapers and Esmond Wickremesinghe’s relationship with Nadesan.

- Denning, M. The Road to Justice – Lectures on courage in the legal profession, cited for the Thomas Erskine example.

Related Historical Events

- Black July (1983) – Communal violence in Sri Lanka; context for Nadesan’s court appearance during the Hewamanne v. de Silva case.

- The 1971 Insurrection in Sri Lanka – Context for Nadesan’s Senate speech and founding of the Civil Rights Movement.

- Pavidi Handa (‘Voice of Clergy’) Movement (1982) – Referendum campaign against parliamentary term extension.

Institutional Recognition

- Peter Pillai Foundation. (1983). Award for Contribution to Human Rights and Social Justice – Presented to S. Nadesan QC.

Additional Context

- Sanmugathasan, N. Recollections of S. Nadesan QC – Trade union legal representation.

- Ranganathan, C. Q.C. Memoirs – Entry into the Bar and mentorship from Nadesan.

- de Silva, A.S. Recollections of S. Nadesan QC. Ceylon Daily News, December 21, 1996. [Referenced for sponsorship to Dharmasoka College]

- Moldrich, D. “He lived – and died – on his feet.” Memorial Tribute, 1986. [Referenced for biographical reflection]

- Sharvananda, Chief Justice. Judicial observations on S. Nadesan QC’s legal stature and versatility.

Notes on Sources

This blog post is based primarily on the comprehensive tribute written by Dr. Reeza Hameed, published in Colombo Telegraph on December 21, 2025, which draws on personal recollections, judicial observations, historical records, and documented cases. While the article itself serves as the foundational source, the references listed above indicate the primary legal documents, constitutional texts, landmark cases, and contextual historical events that are either directly cited in or relevant to understanding Nadesan’s life and legacy.

The cases cited represent milestones in Sri Lankan constitutional and legal jurisprudence, and where specific case details are referenced in the blog post, they are sourced from the legal documentation and historical records cited above.